A new “entretien de la SIF”. Claire Mathieu and Serge Abiteboul interview Susan McGregor who is Assistant Professor at Columbia University and Assistant Director of the Tow Center for Digital Journalism. Besides being a journalist, Susan is also a computer scientist. So, she is really the person to ask about the impact of computer science on journalism.

Professor McGregor © Susan McGregor

B: Susan, who are you?

S: I am assistant professor at the Columbia Graduate School of Journalism and the Assistant Director of the Tow Center for Digital Journalism there. I had a longterm interest in non-fiction writing and got involved in journalism in university, but my academic background is in computer science, information visualization, and educational technology. Prior to joining Columbia, I was the Senior Programmer on the News Graphics team at The Wall Street for four years, and before that was at a start up specializing in real-time event photography. Though I’ve always worked as a programmer, it has always been as a programmer on design teams. Design teams can be a challenge if you come from computer science, because there is a tension between the tendencies of programming and design. Programming prioritizes modular, reusable components and general solutions, while designs should always be as specific to the given situation as possible. My interest in visualization and usability began during a gap year between secondary school and university, part of which I spent working in an administrative role at a large corporation. I observed how incredibly frustrated my co-workers (who were not tech people) were with their computers. Thanks to a CS course I had taken in secondary school I could see places where the software “design” was really just reflecting the underlying technology. Interface decisions – which are essentially communication decisions – were being driven by the technology rather than the user or the task.

Computer science literacy is essential for journalists…

B: How much computer science do you think a good journalist needs to know nowadays?

S: Computer literacy is essential for journalists; in fact, there are enough ways that computer science is important to journalism that a few years ago we began offering a dual-degree program in computer science and journalism at Columbia.

First, journalists must understand digital privacy and security because they have an obligation to protect their sources, so understanding how email and phone metadata can be used to identify those sources is essential. Second – and probably best known – are the roles in newsrooms for those with the engineering skills to build to the tools, platforms and visualizations that are key to the evolving world of digital publishing. Third, computer science concepts like algorithms and machine learning are now a part of nearly every product, service and industry, and influence many areas of public interest. For instance, credit card offers and mortgages are being made available according to algorithms, so understanding their potential for power and bias is crucial to assessing their impact on civil rights. In order to accurately and effectively report on technology in general, more journalists need to understand how these systems work and what they can do. Right now, technology is often covered more from a consumer perspective than from a science perspective. Since joining Columbia, I’ve become more directly aware of the tensions between scientists and journalists. Scientists want their work covered but are rarely happy with the result. Journalists need better scientific understanding, but scientists should also consider putting more effort into their communications with those outside the field. Scientific papers are written for scientific audiences; providing an additional text with more of a focus on accessibility could improve both the quality and reach of science journalism.

… but journalists are essential for people to be informed

B: How do you view the future of journalism given the evolution of computer science in society ?

S: Journalism is increasingly collaborative, with citizen journalists, crowd sourcing of information, and more direct audience interaction. That is a big change from even fifteen years ago! That will continue, though I think we will also see a return to more classic forms, with more in-depth reporting. The Internet has given rise to a lot more content than we used to have, but not necessarily more original reporting. Even if you believe that it requires no special talent or training to be a journalist, you cannot get away from the fact that original reporting takes time. Finding sources takes time; conducting interviews takes time. And while computers can do incredible number-crunching, the kind of inference essential to finding and reporting worthwhile stories is still something that people do better than computers.

Newspaper clip, ©FBI

B: As a journalist, what do you think of natural language processing for extraction of knowledge from text?

S: From what I understand of those particular topics, the most promising prospect for journalists is knowledge collation and discovery. Until only a few years ago, news organizations often had library departments and librarians, and you started a new story or beat by reviewing the “clip file”. That does not exist any more, because most of the archives are digital, and because there isn’t typically a department dedicated to indexing articles in the same way. But if NLP (Natural Language Processing) and entity resolution could help us meaningfully connect coverage across time and sections, it could be a whole new kind of clip file. Many news organization are sitting on decades of coverage without really effective ways to mine and access all that knowledge.

B: How do you define “reporting”?

S: The scientific equivalent of reporting is conducting an experiment or observational study; generating new results or observations. Reporting involves direct observation, interviews, data gathering, media production and analysis. Today, one frequently sees variations of the same news item on different outlets, but they are all based on the same reporting; the volume of content is going up, but the volume of original information is not necessarily increasing. For example, while covering the presidential election in 2008, I learned that virtually all news organizations get their elections data from the Associated Press. Many of these news outlets produce their own maps and charts on election day, but all the news organizations are working from the same data at the same time. It may look diverse, but the source material is identical. Nowadays, you often have several news organizations covering an issue where, realistically, one or two will do. In those cases, I think the others should focus their efforts on underrepresented topics. That’s what we really need: more original reporting and less repetition.

B: You could probably also say that for science. As soon as someone has an interesting idea, everyone flocks to it and repeats it. Now, as a journalist, what do you think of big data analysis?

S: “Big data” is a pretty poorly defined term, encompassing everything from statistics to machine learning, depending on who you ask. The data used in journalism is almost always very small by anybody’s standards. Data-driven journalism, however, is an important and growing part of the field. In the US, we now have outlets based exclusively on data journalism. The popularity of data journalism stems in part, I think, from the fact that the American ideal of journalism is “objective,” and we have a culturally deep-seated notion, carried over from science, that numbers and data are objective, that they embody a truth that is unbiased and apolitical. But what is data? Data is the answer to someone else’s interview questions. Well, what were that person’s motivations? You must be critical of that. Skepticism is a necessary component of journalism, as a profession. At some level you never fully believe any source and such skepticism must extend to data. Corroboration of and context for data are essential.

To me this is also a key point about data and data analysis in journalism: data analysis alone is not journalism. You have to first understand and then present the data’s significance in a way that is relevant and meaningful to your audience. Take food prices, for example. We have good data on that. What if I wrote an article saying that Gala apples were selling for 43 dollars a barrel yesterday? It is a fact – and in that sense “true.” But unless I also include what a barrel cost last week, last month, or last year, it’s meaningless. Is 43 dollars a barrel a lot, or a little? And if I don’t include expert perspectives on why Gala apples sold for 43 dollars a barrel yesterday, it’s not actionable. At its best, journalism provides information with which people can make better decisions about their lives. Without the why it is statistics, not journalism.

Communication, education, and computer technology

Discovery of early homo sapien skulls in Herto, Ethiopia, ©Bradshaw Foundation

B- Sometimes we are frustrated that journalists write so little about critical advances in computer science and, in comparison, so much about discoveries of new bones in Africa, for example.

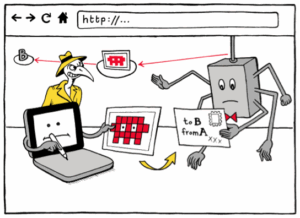

S- Humans are visual creatures. Bones in Africa, you can take pictures. But research discoveries in CS, often they’re not visual. Vision is humans’ highest bandwidth sense, and we know that readers are drawn to visuals in text. I have a pet hypothesis that visualizations can be used, essentially, to turn concepts into episodic memories – as, for example, iconic images, or political propaganda and cartoons do. And because visuals can be consumed at a glance and remembered (relatively) easily, ideas with associated visuals are easier to spread. This is one reason why visuals have been a part of my work on digital security from the beginning.

http vs. https, visualized. © Matteo Farinella & Susan McGregor

B: Speaking of education theory, what do you think of MOOCs (*) ?

S – I doubt MOOCs will persist in their current form, because right now we’re essentially just duplicating the university model online. But I do think that the techniques and technologies being developed through MOOCs will influence regular teaching methods, and there will be an increase in self-organized informal learning. Online videos have and will continue to change education. Interactive exercises with built-in evaluations will continue to be important. Classrooms will be less the place where lectures happen and more where questions get asked. Of course, that possibility is dependent on universal access to good quality internet connections, which is not yet a reality even in many parts of the United States.

Computer science literacy is essential for everyone.

B- What do you think of computer science education at the primary school level?

S – Computational thinking is required literacy for the 21st century. I am not sure how new that idea is: Seymour Papert’s “objects to think with” approach to constructivist education and the development of the Logo programming language happened nearly fifty years ago. I started playing with Logo in primary school, when I was eight. To consider computational thinking a necessary literacy is uncontroversial to me. I can even imagine basic programming used as a method of teaching math. Because I teach adult journalists, I do the reverse: I use story to teach programming.

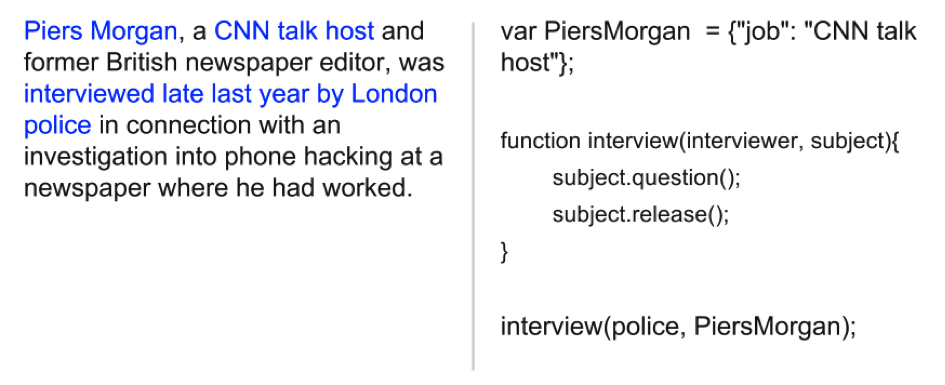

For example, when I teach my students javascript, I teach it as “language,” not as “computing.” That is, I draw a parallel from natural language writing to writing a program. For example, in journalism there is a convention about introducing a new character. When someone is first named in an article, you say something to describe them, such as: “Mr Smith, a 34 year old plumber from Indiana”. Well, that is a variable declaration! Otherwise, if you later refer to Smith without having introduced him, people would not know who you are talking about. The way in which computers “read” programs, especially these very simple programs, is very similar to the way humans read text. You could extend the analogy: the idea of a hyperlink is like including an external library, and so on. The basic grammar of most programming languages is really quite simple compared to the grammar of a natural language: you have conditionals, loops, functions – that is about all.

Sample slide from “Teaching JavaScript as a natural language” presentation delivered at BrooklynJS, February 2014.

B: One last question: what do you think of the Binaire blog? Do you have any advice for us?

S- The time to load the pages is too long. For most news organizations, an increasing proportion of visitor traffic is coming from mobile. The system should sense that the reader has low bandwidth and adapt to it.

B- Is there anything else you would like to add?

S- When it comes to computer science programming and technology, to the audiences who may not be familiar with it, I like to say: you can do it! Douglas Rushkoff once drew a great parallel between programming and driving, and it probably takes the same level of effort to reach basic competency with each. But one big difference is that we see people – all different kinds of people – driving, all the time. Computer science and programming, meanwhile, are invisible, and the people given the most visibility in these fields tend to look alike. Yet they are both arguably essential skills in today’s world. If you want to be able to choose your destination, you must learn to drive a car. Well, in this day and age, if you want to be able to direct yourself in the world, you must learn to think computationally.

Explore computational thinking. You can do it!

Susan McGregor, Columbia University

(*) Mooc, Massive online courses. In French, Flot, Formation en ligne ouverte

Laisser un commentaire